Part of the joy in reading books for a second, third, umpteenth time is that you can come away with an improved understanding. One book I read a few years ago was Patrick Süskind’s The Story Of Mr Sommer (1991). Back then, I remember being underwhelmed by its relatively simple story and, to be honest, none of it really added up. It was the title, presumably, that hampered my experience of the novella as I went in expecting, as suggested, a story about the eponymous Mr Sommer. In doing so I now realise that I missed the point, a point which I feel a reread has sorted out.

Told many years hence, the novella deals with the narrator’s ” old tree climbing days”, those spent growing up in the village of Unternsee, one of many villages running along a lakeside. While the book spans a number of years, the main events are brought to mind by the enigmatic Mr Sommer, resident in the next village, who everyone knew although no one had ever bothered to speak with him.

What makes Mr Sommer memorable, and a vibrant hook for the narrator’s memories, is his penchant for walking:

He would often leave home before daybreak, as the fishermen out on the lake at four in the morning would confirm, and often not get home till late at night, when the moon was already high in the sky. In that time he would cover astonishing distances. To walk right the way round the lake, a distance of some twenty-five miles, in the course of a day was nothing out of the ordinary for Mr Sommer. To make two or three trips into town a day, six miles each way – no problem for Mr Sommer! When we trotted off to school at half past seven in the morning, still rubbing sleep from our eyes, we would encounter a fresh and alert-looking Mr Sommer who had already been walking for hours; coming home tired and hungry at lunchtime, we would be overtaken by Mr Sommer, eating up the ground with enormous strides; and on the evening of the same day, when I took a last peep out of the window before going to bed, I might see the tall, lanky figure of Mr Sommer hurrying shadowly by on the lake road.

While the reasons for Mr Sommer’s perambulatory feats are discussed (claustrophobia? a nervous twitch?) the answers are little more than hearsay and speculation. All around him there’s a sense of loneliness, and in this questions of how we treat others arise. That no one makes the effort to say hello or enquire after his wellbeing leaves Mr Sommer merely trudging on in life, with nothing to experience or stop for, other than necessary distractions like eating and sleeping. It’s the sort of life that can only end in tragic circumstances.

Of the narrator’s life, or where he begins anyway, childhood seems a fun time, one where each day is taken up by the fun of climbing trees and the pretence of flying (“…if I’d just unbuttoned my coat then and held my coat tails in both hands and spread them like wings, why, then the wind would have picked me up altogether, and I would have soared off School Hill with the greatest of ease…”). Soon, though, as with any coming of age story, the coming of age part has to happen.

The Story Of Mr Sommer features a short string of remembered scenes that come together to show the foibles of growing up. Here we have the first stirrings of love with a classmate (“I could have gone on looking at that face for ever, and I did look at it whenever I could, in lessons or during break. But I was careful to do it discreetly, so that no one saw me looking, not evenCarolina herself, because I was terribly shy.”) and, thanks to a gross scene with his piano teacher, a lesson how mean people can be.

That’s life, however, and Süskind cleverly spins all this into a thread about bicycles that runs through the story. When starting out, the narrator has trouble believing such a thing could never support him when it can’t support itself freestanding, but repeated attempts – be it on the bike or in life – soon lead to confidence:

I don’t remember how long it took me to master the dark art of riding a bicycle. All I remember is that I learned it by myself, with a mixture of unwillingness and grim resolve, on my mother’s bicycle, on a slightly sloping forest track where no one could see me…And one time, after many failed attempts, surprisingly suddenly really, I cracked it. I could move – in spite of all my theoretical doubts and my powerful scepticism – freely on two wheels: a mystifying and proud sensation.

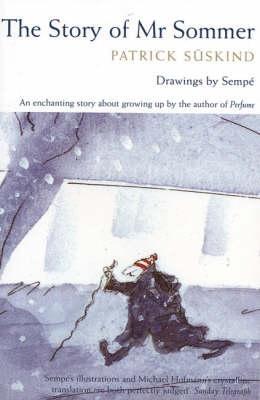

While the narrator got nostalgic, I couldn’t help feeling similar, thanks to the sprinkling of watercolours interspersed with the text, thanks to French artist Sempé. It recalled for me a childhood spent reading the books of Roald Dahl – The Twits, say, or Matilda – all illustrated by Quentin Blake. The Story Of Mr Sommer, however, no matter how lightly the prose makes it seem, is for an older age group, because of darker themes that appear towards the end.

And what of Mr Sommer and his story? Well, this reread showed that the story I was looking for was never there, that it was a mystery, and that’s how it was intended. As a reader you want to understand the character, to ask him why he walks so relentlessly. But when the ending looms and you want to reach out, it’s already too late. There’s been so many chances before and each one not taken.

A friend gave this to me a few years ago and I remember wondering why he’d given me a “kids book” – then I read it and realised that often things that look simple and slim on the surface have far more depth to offer than those that claim to be “clever”.

A great little book to be sure. I haven’t read it in ages and this brings it back to mind. The only point I would make is that not only is it ‘for an older age group’, I don’t think it’s for children at all (though like you, Stewart, it reminded me of Dahl in places, particularly the snot-on-the-keyboard scene). The illustrations just give that impression. It’s serious, grown-up stuff through and through. And that long opening sentence is just a delight.

By older age group, I was thinking teens and above. Saying that, I don’t read teen lit, so don’t know how grim content can get. The lightness of the prose (Hoffman translation – lovely!) makes it a breeze to read and someone could easily enjoy the book just for its scenes, never mind all the depth and misery that lurks beneath.

As to that long opening sentence, let’s just quote it for good measure:

Yowsa! Terrific review that would have me grabbing this from the shelf if I had it. Only $84 on amazon! Heheh. Regardless, it has long walks, tree climbing, bicycles, and dark currents. A must find!

Thanks again for bringing this little jewel to light. As Mr. Summer’s Story, the US edition loses nothing of its wonderful zest and ultimate…what would be the word? Horror? Shock? Awakening? When I think about this story, I’ll always remember the boy in the tree listening to the tap of Mr. Summer’s staff. And I’ll wonder if that lunch under the tree was an intentional thing. Do you think that in some way the boy and Mr Summer each were there for one another in a most unlikely way? It seems as though somehow their path-crossings resulted in each being granted that measure of peace. Not what I expected, which made it all the better.