It’s called Scotland’s shame, the sectarianism that has attached itself to Scottish society and festers therein. The absorption of Ireland’s exiles in the nineteenth century saw Catholicism take steps into the country, much to the chagrin of the Protestant ‘indigènes’, and the rest, as they say, is history. Although it’s not history per se as the divide created then is still very much alive today, most prominently masquerading around within the national sport: football.

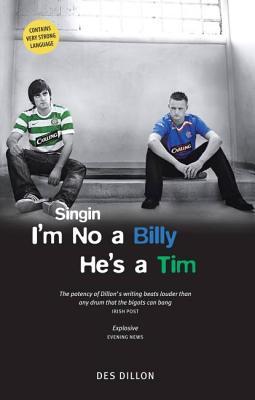

Des Dillon’s play, Singin I’m No A Billy He’s A Tim (2005) tackles sectarianism head on. Since its initial performance at the Edinburgh Festival, the play has gone on to tour both Scotland and Northern Ireland, and it was even used by the then Scottish Executive to tackle the issue of bigotry at school level. By turning the spotlight on two football fans — Tim and Billy, immediately defined by their heavy brush stroke of a name — supporting a team on either side of the divide, Dillon creates a dialogue that explores sectarianism.

Tim, in the green and white, is a Glasgow Celtic fan., and therefore of Catholic stock. It’s not long before Billy is calling him on singing a song about the Irish revolutionary Michael Collins:

Billy: I wish you lot would shut up wi that shite.

Tim: It’s my heritage.

Billy: Yer heritage!

Tim: There’s nothin wrong wi rememberin yer heritage.

Billy: I bet ye’ve never even been in Ireland. (Beat as Tim squirms) Have ye?

Tim: I’m not tellin you where I’ve been an where I’ve not.

A beat, then:

Billy: Ye’ve never been have ye? (Tim ignores him) Answer me then.

Tim: So! What if I haven’t?

Billy: Yees’re aw the same — rattlin oan aboot a place ye’ve never been. If I had my way I’d send yees aw back to fuckin tattie land.

In the dialogue between the two, there’s underlying irony to be had with Billy (“Ma heritage goes straight as a die to Ulster.”), a Glasgow Rangers fan, and therefore Protestant. Situations in real life are, of course, more complicated, but Billy and Tim prove adequate mouthpieces through which the fallacies and the hatred that lie at the heart of the problem can be aired. History, politics, religion, and institutions are all paid a visit for their role in the sectarianism of today.

The scene is a Glasgow jail, on match day. Not just any match day, but the clash of the Old Firm: Rangers and Celtic. Both Billy and Tim, however, have landed themselves in the cells. In such a confined space, there’s little more they can do than talk and take broad swipes at each other, unleashing the vitriol as it comes pouring out, and each eager to take the upper hand. While they are able to trot out all the cliches, the moronic arguments that have seen nothing but a stalemate lasting decades, their own ignorance and naivete in getting caught up in the cycle of bigotry reveals itself, from songs sung in the name of sport —

Billy: Hello — Hello — we are the Billy boys, Hello — Hello — you’ll know us by our noise, We’re up to our knees in Fenion blood…

— through outright insulting —

Tim: …into these (rhythm of the old Coke advert) Orange-Mason-hand-shakin-Ulster-lovin-finger-ticklin-Tim-hatin-goat-buckin-Proddy-fuckin-bastards.

As the invective becomes exhausted, it seems the only way forward is for reconciliation, and in an ideal world this is what would happen. Dillon’s play explores this ideal world, becoming one along the way, as the notions of how to solve the problems of sectarianism manifests itself within the two players. In truth it happens all too easily, but the characters do come to it via logical means.

Although the skin of the play wraps around bigotry in Scotland, the bones are far more generic, for sectarianism is an issue that affects far flung areas of the world, like the tit-for-tat between Israel and Palestine or the genocide of the Balkan conflict — all disputes that have no end in sight. Dillon’s play works on the basis that common ground needs to be found between the sparring parties and from there, mutual understanding can be fostered, goalposts set, and favourable results achieved. It’s a simplistic enough idea, and hardly revolutionary, but it works in the context of opening up dialogue on the subject.

Tim: Look — I think everybody’s a bigot. We’ve all got bigotry. Every single person’s got bigotry for somethin.

The closing stage, where a symbolic unification occurs is poignant, for gone are the bilious songs that characterised both men and their upbringing, and in comes one that represents Scotland as a whole, the bigotry driven out.

The merits of the play would be best experienced in a theatre rather than on the page, as, given the subject matter, it’s a narrative that could bring people to the theatre who would never think to otherwise. While it’s laudable that it could be used to dispell myths, quash rumours, and educate people on the sectarian divide, its downside is that the casual banter and reheated arguments, especially to those who have heard them all before, become more of a novelty than a criticism. Sectarianism is Scotland’s ‘elephant in the room’ and more literature should seek to attack it. Singin I’m No A Billy He’s A Tim opens up dialogue, and entertains in doing so.

I know little about political or religious sectarianism, either in Glasgow, Ireland, or anywhere else, but this sounds like it is quite accessible for anyone interested in the divide that doesn’t particularly care about football. I get the impression that it’s not entirely subtle, calling the characters Billy and Tim (Tim Malloys? I’m guessing the Billy is a real reference, too.)

It’s interesting that you say that this play would be better experienced on stage, rather than being read, as more well-known playwrights, such as Ibsen and Pirandello, say plays are for the literary, and as such, are better read.

“goalposts set, and favourable results achieved” – excellent review, Stewart.

Yes, Billy refers to William III. Or King Billy as he’s colloquially known. Goes back to the Battle of the Boyne.

Nice. Want to see it now. Might wait a while before it’s performed in Kenya yet… another place where sectarianism rules.

Hm. It sounds a bit pat to be honest. I’m Scottish, my mother’s side of the family are Catholic, my father’s Protestant (actually, atheist, but that counts as Protestant in Scotland) so I’m pretty familiar with this issue. It sounds a little worthy, and a little unrealistic. Scottish sectarianism is a very ugly beast, plenty of individuals reconcile but the hatred continues. There was no small tension about my parents marrying, and while it’s not nearly as bad as it was, just a couple of years back I had a very uncomfortable cab journey with a cabbie with an RFC ring who spent the trip telling me of his hatred for Catholics.

The best treatment I’ve seen of Scottish sectarianism was Ian Rankin’s Mortal Causes, easily the best of his I’ve read (also the most recent of his I’ve read, he shows clear development as a writer over the first few books). He explores it to good effect, offering no solutions beyond the antiseptic of daylight.

Come to think of it, you live in Glasgow don’t you Stewart? You know all this better than I do then, my knowledge now is from family and trips back up, I live down in London.

Yes, Max, I’m in Glasgow. I do agree that historical differences aren’t just wiped out by a few allegorical hours in a jail cell, but I don’t think this is a work that full-on challenges sectarianism. It will open dialogue — as has been evidenced with politicians looking to adapt it for schools — but, for literature anyway, we need a fiery polemic to get people talking. Here the comedy — or the novelty of a play in a Glasgow dialect, as I’d guess its largest crowds are Glaswegian football fans, for people who would rarely take a trip to the theatre — sort of dilutes any power it has pretensions of having.

Iv seen the play and it’s good, Iv saw and been in the situations it shows and some really funny moments. nobody said it would end secterianism but it does show when you watch it how ridiculous and clueless some bigots are.

Hi,

My son plays Billy in this play and its his Theatre Company who is taking the play on tour.

The play is attracting 70% of an audience who have never been to theatre before and going down a storm with both sides laughing at themselves and each other really…worth seeing visit http://www.nlptheatre.co.uk for dates and venues..just back from ireland where it went down a storm too.