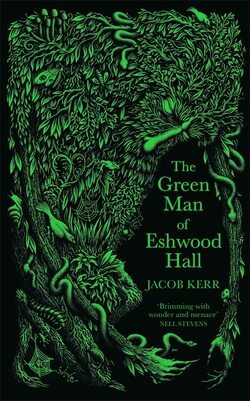

The Green Man of Eshwood Hall (2022) is the first of an unknown number by Jacob Kerr set in Northalbion, a fictional spin on Northumberland. Set over 1962, it’s a mostly enchanting tale of a young girl who spends her spare time in the woods near her new house and the discoveries she makes.

Eshwood Hall has been occupied by the Claibornes, the only surviving member living upstairs, mostly confined to bed. Around her a skeleton crew works tending the garden and cooking meals. It’s into this employ the Whipper family come, with peripatetic odd-job man Ray’s family once more uprooted to the whims of his work. With him is his wife Gerry, who suffers an undisclosed heart issue, the younger children Annie and newborn Raymond. And forced to truant to assist her mother is thirteen year old Izzy, whom the narration, joyfully sprinkled with Northumbrian dialect, hovers mostly over.

When Izzy takes to the woods she meets the eponymous Green Man, a somewhat ambiguous character delightfully fluid in his seemingly corporeal form of leaves, branches, and berries. Though he seems genial in his willingness to assist Izzy with her problems in exchange for something, there’s echoes of WW Jacob’s classic short, The Monkey’s Paw, as his bargains and their results are not always as intended.

The prose is lyrical, observing nature wonderfully, a rich awareness of flora and fauna and how the seasons change them, but finds no deeper beauty or cause for reflection. There’s a lovely section of May Day celebrations with much English folk tradition on show. And the folksy delivery of the tale brings a real sense of listening to a storyteller with all eyes on him.

Overall it feels like an enchanted adventure in folk horror drag, and when the horrific does spill out, there’s a nice ambiguity to it all. But the book is somewhat patchy, meandering this way and that, its focus and tone shifting. Maybe the book’s underlying focus is somewhat ecological, about destroying rural lands and dooming longstanding ways of life, and serves to highlight that nature is still out there, on the edges of civilization, with the power to enchant us, but we keep building and pushing it away.